In Memoriam: Kay Parley, RPN (Registered Psychiatric Nurse) Mar 19, 1923 - May 22, 2025

Canadian Psychedelic Nursing Pioneer, who worked with Humphrey Osmond, treating patients with LSD in the 1950's

By Andrew Penn, UC San Francisco, OPENurses and Erika Dyck, University of Saskatchewan

Kay Parley, a registered psychiatric nurse (RPN in Canada) passed away after a brief illness on May 22, 2025, at 102 years of age in Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada. In February 2024, along with postdoctoral historian Zoë Dubus (from the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon), we visited Kay for two days to interview her about her experiences as an early psychedelic nurse.

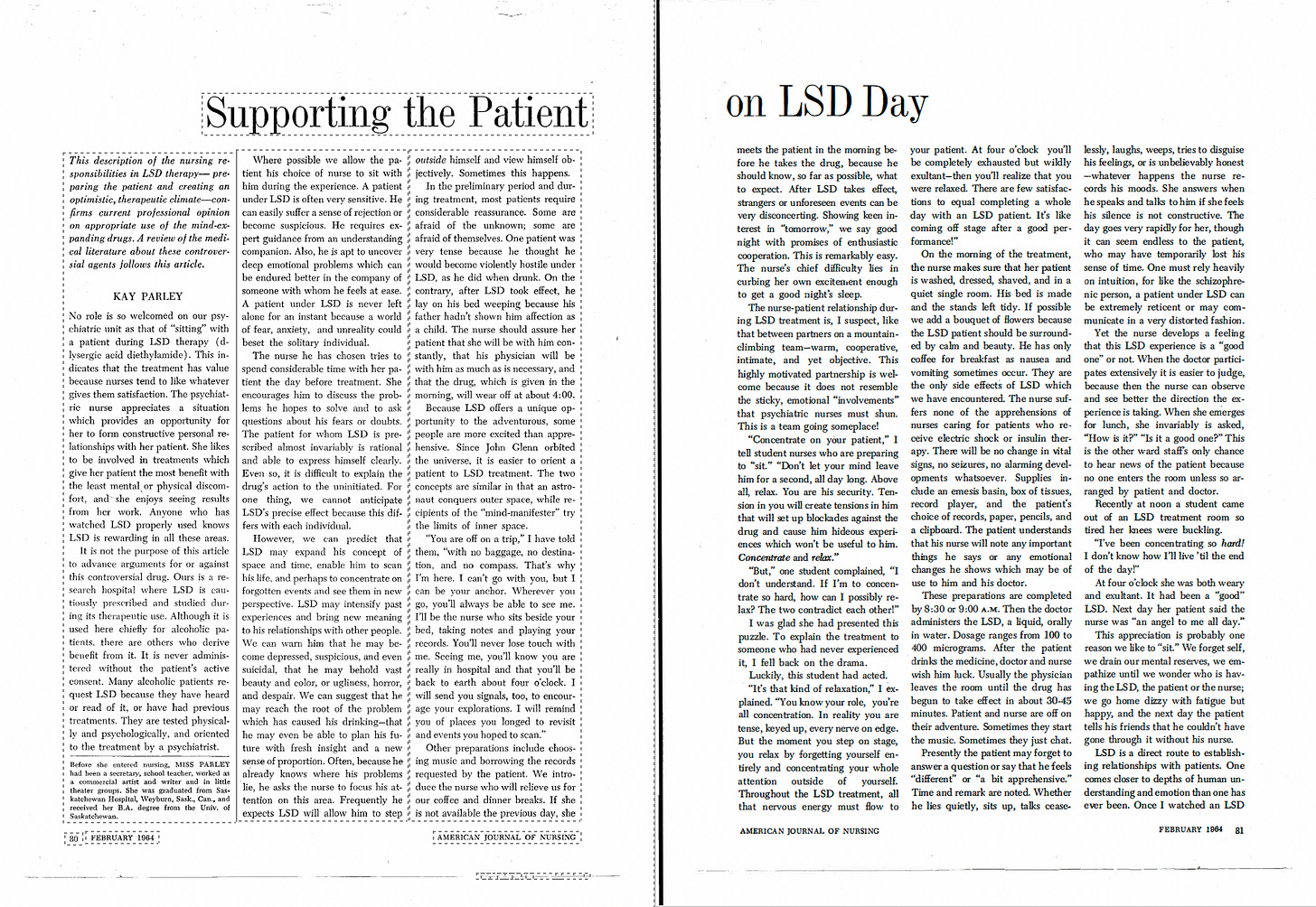

Andrew had written to her in the height of COVID19 at the suggestion of her cousin, the filmmaker, Judith Silverthorne, who told him that Kay didn’t use a computer, and her hearing loss precluded her use of a phone, but she would promptly respond to any letter she received. Andrew sent a letter along with his recently published article in the American Journal of Nursing, the first in 57 years since Kay’s description working with Drs Humphry Osmond and Abram Hoffer, providing LSD experiences to staff and patients at psychiatric hospitals in Saskatchewan, Canada between 1951 and 1967. Kay had described her experiences as a nurse guide, or “sitter” during these LSD sessions In a 1964 article in the American Journal of Nursing entitled “Supporting the Patient on LSD Day.” She responded back promptly, as promised, with a typewritten letter expressing appreciation and an invitation to visit.

We visited in February 2024, during a warm snap in Regina, which lies 100 miles north of the border with Montana, where it was a balmy 20 degrees Fahrenheit, 40 degrees warmer than the week before.

She shared with us her experience of becoming a nurse and working at Weyburn that came after her own experience of mental illness. In 1948, at the age of 24, while she was training to be a radio actor for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) in Toronto, Kay experienced her first episode of an illness that had run through her family for at least two generations before – manic-depression. Both her father and her grandfather had become stricken with manic depression and been treated at Weyburn Hospital where they lived on and off throughout her childhood. Her father entered the hospital when Kay was only seven years old. Kay’s mother brought her back to Saskatchewan after she became ill, and she was admitted to the Saskatchewan Provincial Mental Hospital at Weyburn, a place that she had feared as a place that had taken her father from her, but she later grew to love that hospital.

When we asked Kay about her first impressions of Weyburn as a newly admitted patient, she told us,

“Castle! Palace! Oh beautiful big building. I just loved it. Got these steps and then marble floors, shiny staircase oh wow. But I thought they'd probably put me in a cell. But they didn't, you see. So, everything started getting better and better!”

In the hospital, Kay met her Grandfather Parley for the first time, who had become a respected elder member of the patient community there. She also met her father, who she had not seen she was seven years old. She recounted these experiences in her memoir, Inside the Mental, (University of Regina Press, 2016) that she wrote at the age of 93 (and was interviewed by the CBC about). She stayed at the hospital in Weyburn for 10 months until she recovered from her episode. She remembered her time in the hospital as quite pleasant. She reconnected with her relatives and explored her talents as a writer. At one point Kay became the editor of the hospital newspaper, The Torch, which began her writing career – a passion she continued until the end of her life, maintaining a regular column in her local newspaper in Regina until the week before her death.

During her hospital stay, Kay was inspired by many of her experiences and decided to enter the nursing profession and return to the hospital in a different capacity. She began nursing training in 1956 and returned to Weyburn as a nurse working on various wards within the hospital. She arrived as the new hospital superintendent, Dr Humphry Osmond was reforming the hospital policies, practices, and even ideas about mental illness itself. One of his innovations was to use LSD (d-lysergic acid diethylamide), then a relatively new pharmaceutical drug made by the Sandoz corporation in Switzerland, for treating alcoholics. Kay was one of several nurses who would “sit” with patients all day as they experienced the effects of LSD, often over the course of 8 to 12 hours. She wrote of this experience in her 1964 American Journal of Nursing article “Supporting the Patient on LSD Day”:

“No role is so welcomed on our psychiatric unit as that of "sitting" with a patient during LSD therapy (d-lysergic acid diethylamide). This indicates that the treatment has value because nurses tend to like whatever gives them satisfaction. The psychiatric nurse appreciates a situation which provides an opportunity for her to form constructive personal relationships with her patient. She likes to be involved in treatments which give her patient the most benefit with the least mental or physical discomfort, and she enjoys seeing results from her work. Anyone who has watched LSD properly used knows LSD is rewarding in all these areas.”

She went on to talk about the role of the nurse in maintaining safety and to encourage the patient to benefit from the experience

“Because LSD offers a unique opportunity to the adventurous, some people are more excited than apprehensive. Since John Glenn orbited the universe, it is easier to orient a patient to LSD treatment. The two concepts are similar in that an astronaut conquers outer space, while recipients of the "mind-manifester" try the limits of inner space.

"You are off on a trip," I have told them, "with no baggage, no destination, and no compass. That's why I'm here. I can't go with you, but I can be your anchor. Wherever you go, you'll always be able to see me. I'll be the nurse who sits beside your bed, taking notes and playing your records. You'll never lose touch with me. Seeing me, you'll know you are really in hospital and that you'll be back to earth about four o'clock. I will send you signals, too, to encourage your explorations. I will remind you of places you longed to revisit and events you hoped to scan."

Unaware of the cultural and political upheavals that would surround LSD in the ensuing years, Kay wrote her account with unsentimental clarity and pragmatism, eschewing mysticism and centering the relationship between the nurse and the patient as the primary means of supporting their experience.

“The nurse-patient relationship during LSD treatment is, I suspect, like that between partners on a mountain climbing team-warm, cooperative, intimate, and yet objective. “

At the time that Kay was trained to “sit LSD” it was common for nurses and other professionals working in this therapy to have their own LSD experience to better understand the experience of the patient and to train the intuition of the nurse when working with a patient experiencing LSD. Although Osmond recommended this approach to increase clinician’s empathy for patients undergoing the treatment, in Kay’s case he thought it was ill advised. Kay had, in her words, “had a breakdown.” Much to her surprise, she was offered LSD by Francis Huxley. Francis (the nephew of Aldous Huxley) was an anthropologist doing field work at Weyburn and housesitting for the Osmonds. He invited Kay for tea, and asked if she might instead prefer to try LSD. She impishly agreed and described her one and only psychedelic experience, which she described as a combination of wonder and distress, but one that ended with Huxley reminding her, “You might as well face it, Kay. You’re one of the strong ones,” words she said she never forgot.

When we interviewed her in February 2024, Kay reflected on her time as both a patient of the hospital and a member of its staff as being part of a community that extended beyond the hospital. She spoke of how she was, upon discharge, encouraged to be an ambassador for the hospital and its patients, and how she learned never to hide her experiences or her illness.

Kay emphasized the role that community had in the recovery of patients in the hospital, remarking,

“It (was) definitely a community. Absolutely. I can't get over the fact they can't understand that the mental hospital is a community, you know? I guess so many people saying “community?!”, that's what it was. Everybody knew everybody.

And there was a lot of cooperation in that place and there's so much going on, you know, all sorts of sports on the grounds and things going on. And people knowing each other. And we had a pharmacy and a hospital, 2 hospitals and one for the male patients, one for the female. And we had hairdressers, Barber. Drug store. You name it, a ballpark and the tennis court. You name it, we had it. There was a lot of interaction. We were a community, no doubt about it. People knew each other and they counted on each other. I can remember when I was a patient, I was sick one day.

And one of the ladies on the Parole ward (patients that were allowed to leave the hospital and return), as we called it, went all the way downtown to buy me something for my sore throat. I’ve always remembered that. That's the kind of community it was. People did things for you.”

Kay went on to teach nursing and continued to write and paint, writing 6 other books in addition to her regular contributions to the newspaper and her memoir, Inside the Mental.

When we visited Kay in 2024, the first thing that we noticed was her laughter. Her sentences were often punctuated by her infectious giggle. The next thing we noticed was her indomitable energy as we talked for almost 4 hours about her life, her illness, her experiences as a nurse, and her thoughts about the future of psychedelic treatments and nursing. It was also clear how loved she was by her cousin Judith Silverthorne and her friends who joined us to celebrate her 101st birthday at the assisted living facility where she lived.

Our trip was funded by the many donors to our GoFundMe campaign and the Canada Research Chair Program and Ben Schubert of ImageCapture Media assured that all of the incredible conversation was captured for posterity and for future generations to appreciate. The interviews from that visit have been transcribed and the recordings are being edited into a format that will allow Kay’s story to reach even more nurses, those interested in psychedelics, and those who will be able to benefit from their healing potential. If you would like to support that effort, please consider a contribution to the project here.

Andy,

Just a wonderful article about the contributions of one person who touched the lives of so many. She was one of the strong ones!

I love reading about Kay Paley and her perspective about nursing, mental illness and psychedelics. Special to our profession! You are a guiding torch too!