I woke at an ungodly early hour on Wednesday, Nov 6th, glanced at my phone to confirm my fears about the election results the night before, and headed to the airport for a 6:45a.m. flight to a conference. As I stood in the TSA line, I looked at the cross-section of America around me. I felt something primitive well up in me – unconsciously sizing up who might be a threat and who might be an ally, attempting to parse humanity based on crude heuristics – “What about the guy with the camouflage cap? Does he support preventing a woman from controlling her own body? Does he support denying my queer and trans family and friends life-saving health care? Would the woman with the rainbow pin on her backpack resist the mass deportation of immigrants?” I felt that most ancient part of my brain coming online – “are you like me, or are you different? Friend or foe?”

Watching the election results roll in this week underscored the reality that we are living in two Americas. But unlike the geographic division in the 19th century that preceded a bloody civil war, our divides are no longer geographic, they are within us. Even many seemingly “red” or “blue” states are more purple under closer inspection. “Those people” whom we disparage often live down the street from us. Our children go to school together.

As the plane ascended, I watched the golden light of dawn scrape across the vast Sierra Nevada mountains, tears began to fall as I allowed myself to feel the grief that had been eclipsed by shocked defeat the day before. I found myself wondering, “how did we come to believe we are so separate from each other, so much that a campaign based on scapegoating and othering could be so successful?”

Evolution maintained tension between self and other as something that increases survival: it’s a conserved trait. “Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” is a concise, if dense observation in biology that the development of an individual organism (ontogeny) broadly mirrors the process of evolution through which that species emerged over time (phylogeny). For example, in utero, human fetuses briefly have vestigial tails not dissimilar from those that would have been found on our primate ancestors, but that tail is later subsumed into the body and becomes our coccyx before we are born.

Our relationship between self and other has travelled a similar path of evolution. The first task of the infant’s immune system is to differentiate our own cells from the sea of microbes in which we all live in the world. We must learn to differentiate a pathogen from our own cells. Get it wrong and miss a threatening bacteria or virus and we die. Get it wrong and mistake our own cells as a threat and we develop an autoimmune disease. However, much of the microbial world is indifferent to our existence and not a pathogen. The body must also learn to identify and ignore these neutral actors.

Similarly, that capacity for seeing other people as a potential threats and responding accordingly once kept our species alive long enough to reproduce. But to see another as a threat, one must first see this person as a “other”, hostile and not neutral. As we develop as infants, it’s believed that we see ourselves as part of our mother for the first year or so, until the process of individuation begins, when we begin to see ourselves as a separate people. However, the cost of our independence can be an illusion of separateness from others. If we fail to differentiate the neutral from the dangerous, we risk living in the delusional kingdom of one, led by the mighty “I” that fights a million battles against the threats (imagined or real) of other kingdoms.

As I stood in that TSA line, I felt those primitive parts of my brain, the parts that look for and respond to threat by readying for a fight, coming online. I averted my eyes. I did not smile. I felt my body tense, ready for conflict, even though there was no apparent threat at hand. Those impulsive and aggressive parts of my brain that may have kept my distant ancestors safe from threat and also ran the show when I was a toddler, but hopefully, I have since evolved beyond this place of primitive reactivity. The existence of civil society is predicated on our ability to appeal to the better angels of our nature, and to inhibit these primitive impulses, as Lincoln implored in his first inaugural address.

Our nation is more divided than ever, which can only happen when “othering” is rampant. Yet, when we feel in peril, we often retreat to the safety of groups of people who are like us and reject the stranger as a potential risk, as I did in that TSA line.

How will we ever find our way out of this mess?

The Vietnamese Buddhist monk, Thich Nhat Hanh said, “we are here to awaken from the illusion of our separateness.” Before we can do that, we must first feel solid within ourselves and our immediate communities. There are many people right now who are simply numb or in terror, trying to make sense of the election, trying to plan how to keep themselves, their families, and their communities safe in a country that will soon be ruled by an administration that is openly hostile towards women, the LGBTQI+ population, immigrants, democrats, and anyone who dares to stand up to them. To anyone in this state, I offer a variant of the wobbly Joe Hill’s suggestion: “Mourn first. Then organize.” Take all the time you need. Don’t look at the news for a few days. Feel all the feelings. Scream into the void if that’s what’s needed. Make room for the grief of that which we have loved and lost, but as grief expert Francis Weller suggests we also feel grief for that which we expected and did not receive and also, the grief of the world.

I’ve heard about some members of our community who are most vulnerable to the forthcoming changes even feeling suicidal last week. To you I say: I see you, I will use what power I have to help shield you, and hope that you will, in the words of Galway Kinnell’s poem, Wait:

Wait, for now.

Distrust everything if you have to.

But trust the hours. Haven’t they

carried you everywhere, up to now?

(the rest of the poem can be found here)

The opposite of othering is neighboring. Start with those closest to you - check in on your people: your family, your friends, your allies and communities. Send a text, call, go for a walk. See what they need. Love them. Be relentlessly kind. A friend recently noted that the constant noise of social media posting went quiet after the election, perhaps because it was the text threads were busy with close circles of friends connecting and planning walks in the cool, autumnal weather, figuring out together what’s next, making these networks stronger. Historian and activist Rebecca Solnit wrote in “A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster” that what we will need in the days ahead is mutual aid. The calvary is not coming. We are most certainly going to take care of each other in the months and years ahead. (More practical tips on resilience and resistance in the years ahead here).

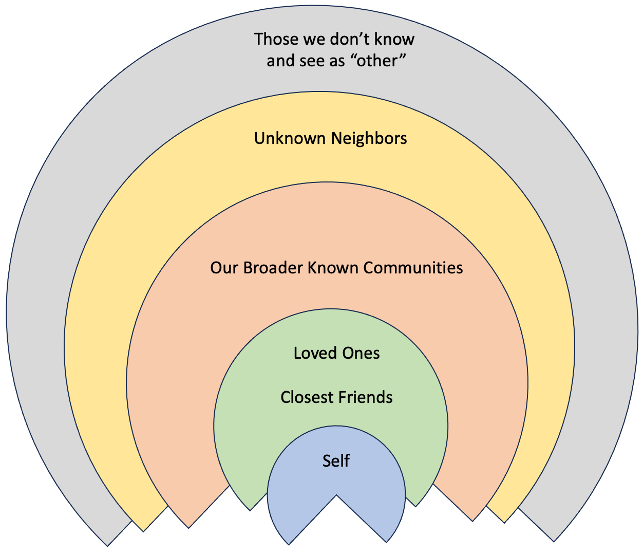

But then, once we have solidified our personal and community foundations, what do we organize? What if we were to, in the words of chef and founder of World Central Kitchen, Jose Andres “Build longer tables, not taller walls”? What if we first took care of those closest to us – inviting our families and closest friends to these tables, and then extend a seat to our larger, known communities? If there is still energy left, continuing this invitation to those who we do not know – our neighbors, to grow these communities that reflect our shared values. Finally, fortified by this, what if we gently extended our care and curiosity towards those who we consider “other?” Might we find complexity and nuance in those who have been portrayed only in two dimensions? Might we find that we’ve been pitted against each other by those who stand to benefit from our divisions, be it politicians or social media companies? Aldous Huxley once wrote that “The propagandist's purpose is to make one set of people forget that certain other sets of people are human.” Curiosity about the other is an act of resistance to those who benefit from division and discord.

To be clear, I am not suggesting that all ideas, and certainly not all behaviors should be tolerated or endured. This is the paradox of tolerance that Karl Popper described in which tolerance is extended towards the intolerant in liberal societies until intolerant forces take power (often through violence) and use that power to silence the tolerant. Injustice in all its forms, must be actively resisted and our fundamental freedoms vigorously protected.

The meditation practice of loving-kindness, or metta follows a similar invitation to the table, first offering oneself the words “May I be happy. May I be well. May I be safe. May I be peaceful and at ease.” These same sentiments are then quietly extended in meditation or prayer towards those whom we are closest, then to neighbors and acquaintances, and then, paradoxically, towards those who we find most vexing and difficult – may you be happy, may you be safe, may you be peaceful and at ease. This practice of extending goodwill not only to those who we care for, but also to those with whom we deeply disagree is not an easy one. Like all practices, it requires persistence and discipline.

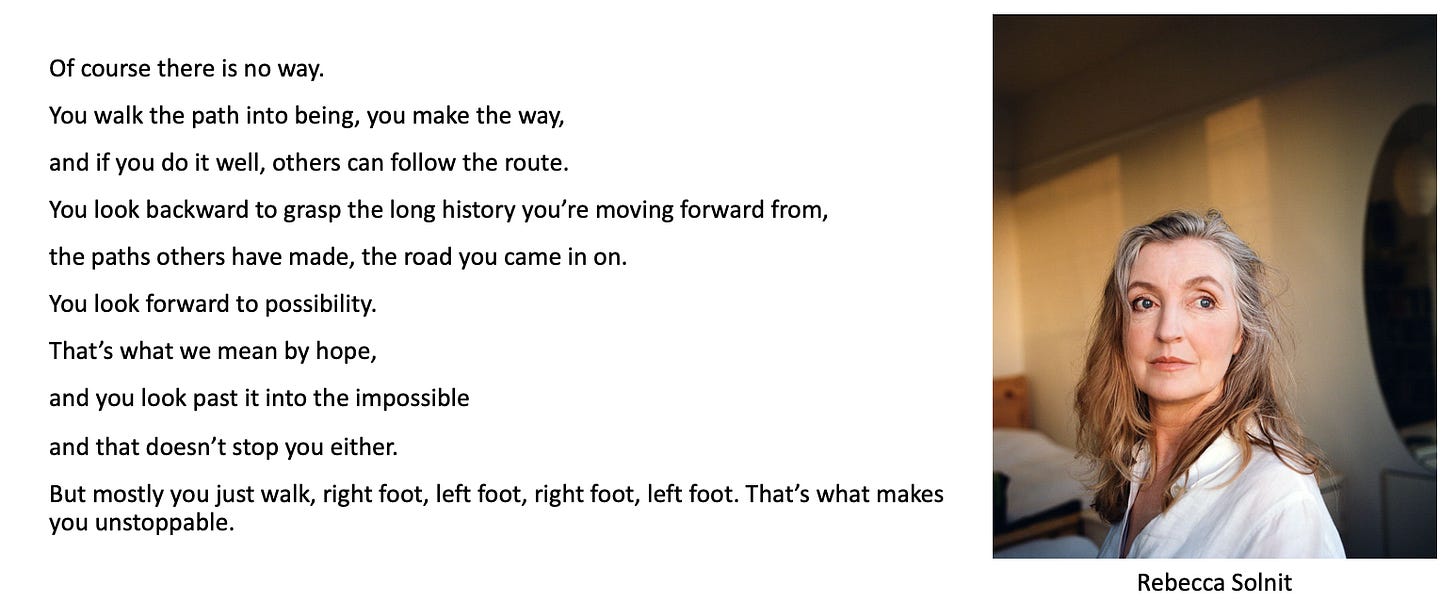

Another practice will need cultivate is hope. Hope is not a state, but rather a discipline, as Rebecca Solnit noted in her 2003 piece “The Case for Hope” (below) she notes that we bring the path into being by walking it regularly, and I posit, that we make a wider and deeper path the more people we bring along with us.

(The remainder of the piece can be found here)

Separateness and antipathy towards those who are not like us may be part of the phylogeny of our species, but they need not dictate our ontogeny or our society. Our freedoms and rights may certainly be under attack by those who stand to benefit from our divisions, but we retain the freedom of deciding how to respond. Just as hope is an action, love is not passive. Far from it, the loving protection of a friend, of a neighbor, of a member of our community, or people who we have never met before, will need to be fierce, and it is within these networks of relationship that we cultivate this hope, love, and protection. That’s what makes us unstoppable.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

[To be clear, I realize how shielded from this that I am as an (increasingly) old, white, cis-gendered, US citizen, college educated, able-bodied, neurotypical, employed with health insurance, person living in San Francisco, a solidly blue city within a solidly blue state. I worry for all of us, but it's the queer, disabled, immigrant, poor people living in states where such buffers do not exist that I worry far more about than myself.]

Thank you, Andrew. A beautiful reflection.

The way forward is loving kindness. Not the transactional, bypass-y version of love but the sturdy kind that gets up early to deliver food and sits with a hurting human, the kind that holds space and bears witness and offers support with renewed attention to the suffering all around us. I have been surprised by the rising and expansion of tenderness within my heart towards the "other". I allow this tenderness and attention lead me these days. I also know that I will fight with body and soul for the safety of my trans grandchild. May we abide in the beloved.

You wrote so beautifully and I always learn something. Thanks for sharing these thoughts and encouragements.